Of all the many battlefronts in the Second Great War (1885–1893 Cristos Reckoning), none evokes more sorrow, grief and anger than Hevagne. Though the entire war involved a horrific cost in lives, treasure, and environmental devastation, perhaps nowhere else was the tragic futility of this conflict on greater display.

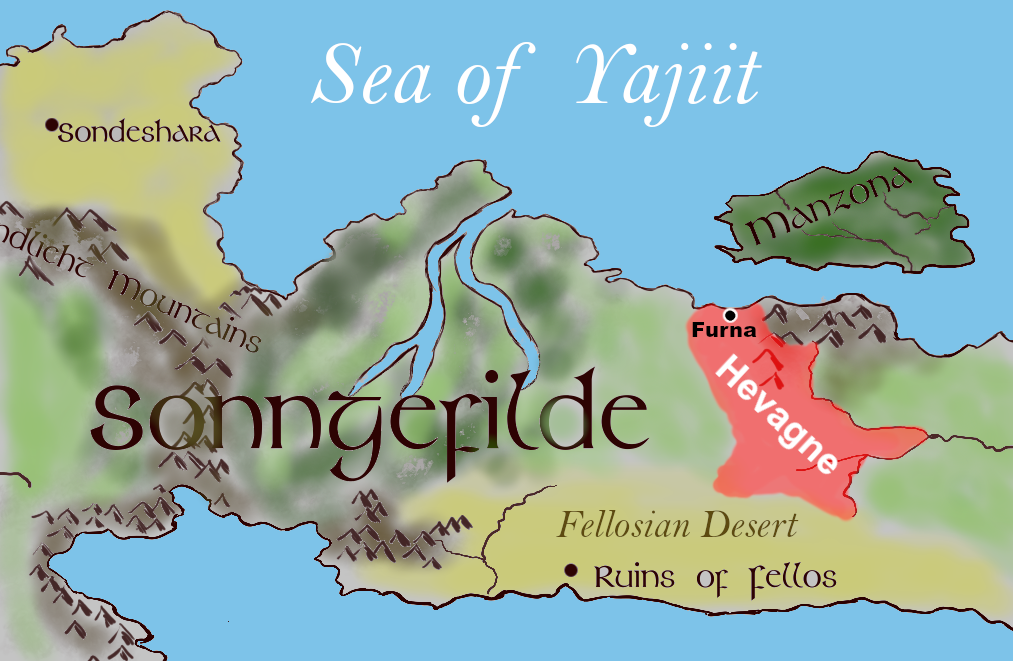

The Republic of Hevagne (pronounced he-VANE), sometimes called the Grave of Empires, is a sparsely-populated and impoverished nation in eastern Sonngefilde. It has a tropical, semi-arid climate, and is mostly landlocked, except for the port of Furna on its northwestern border. It is a harsh and rocky land, marking a transition zone between the high mountains to the north and the brutal Fellosian Desert to the south. Most of its indigenous people, the Hevagni (he-VAY-nee), are nomadic herders, following their flocks of sheep and goats as they follow the seasonal rains. Those who chose a more sedentary existence settled mostly in small villages along the inland trade routes, but they maintained familial and cultural ties with the nomads of the backcountry. Furna was the only city of appreciable size, and though it had claimed to act as the seat of government for centuries, in practice it had little influence over most of the interior.

For millennia, the lives of the Hevagni changed very little. Foreigners would pass through their land somewhat frequently, as it offered the only viable land route through the continent’s interior. Merchants would trade food, clothing and other essentials for derivatives of the poppy plant, which was gathered from remote fields and valleys and used for cooking, medicine, and intoxicants. From time to time foreign armies would come and occupy the land, intent on controlling the trade route, the poppy, or both. Such efforts were doomed to failure; the nomads did not recognize kings or borders, and they were ferocious fighters when provoked.

The Second Great War marked a dramatic change for Hevagne, one that forced its people to engage with the world at large. The armies of the Triad Nations, led by the Republic of Telvar, invaded from the east, as so many armies had before them—but this time they had motorized vehicles, and airships, and powerful creatures summoned from the outer planes. The Triad was not interested in occupying the interior; they only intended to move their forces through Hevagne as quickly as possible, to seize the port of Furna and establish a forward base for their air force. If they succeeded, the Allies’ control of the Sea of Yajiit would be compromised, and the great cities of Athos, Pyralis, and Sondeshara would all come under threat from Telvari bombers.

The Triad had negotiated in secret with the nomadic leaders, bribing them handsomely in exchange for letting their armies pass through the land unmolested. Most of the nomads held little love for Furna, and were content to let the Triad have it. But one of these tribes had second thoughts about the arrangement—for reasons that are still unclear, and argued intensely by historians—and brought word to Furna that the invasion was imminent. The city-dwellers passed the word to the Allies, and a defensive force was quickly dispatched. Hundreds of ships rushed to Furna, carrying thousands of troops and countless tons of materiel. Rail lines were built in record time to deliver these weapons and personnel to Hevagne’s interior. The two armies both rushed to secure the largest and most important passes, and this was where they clashed.

The Triad’s hopes had depended on moving swiftly through the interior, taking Furna by surprise before their supplies were depleted. Rather than retreat when this effort failed, General Hiradal Mzade ordered his troops to dig in. The Allies, under Field Marshal Renaldo Bertoulli, did likewise. The conflict that followed was slow, grueling, and brutal. With impassable mountains to the north and unforgiving desert to the south, neither force was in a position to outflank the other. Each side had supply lines the other had no way of threatening. A head-on assault against the enemy fortifications was suicidal. Hevagne was also, frankly, not the most important theater of war to either side’s objectives: as long as the enemy was kept from advancing, the commanders had other fronts where their resources were more urgently needed. The result was a long, ugly stalemate: each side continued sending in enough weapons and troops to hold the line, but not enough to overwhelm the enemy’s defenses and obtain a decisive victory.

If different generals had been in command, Hevagne might have gone down in history as a quiet footnote; both sides might have settled into their defensive fortifications, kept watch on the opposing side, and waited for the outcome of the war to be decided elsewhere. Unfortunately, Mzade and Bertoulli were not quiet men. Both were decorated veterans of the First Great War, stubborn and prideful, and they no interest in being in anyone’s footnotes. Mzade had convinced Telvar’s military junta that he could bring the Allies to the bargaining table with a swift and victorious campaign. Bertoulli had political aspirations in his native Pyralis, and believed that driving the Telvari out of Sonngefilde was the key to realizing his ambitions. So both men made dangerous gambles to break the stalemate, took unnecessary risks, and squandered lives and resources in the process.

And it was the common soldiers—people like Natasha Volkova—who paid the price.